Earlier this week I had the opportunity to attend a joint meeting between the city and the school district. Each year leaders from both entities come together to share their respective agenda priorities on matters ultimately significant to the larger community. It’s also a chance to put faces with names we know such as the mayor or city manager or council members to our board of trustees and superintendent along with senior staff that support a variety of city and school functions. Several topics were discussed but the two that loomed large were school funding and property tax reform. Texas is one of seven states with no income tax and consequently relies most heavily on sales and other taxes for its revenue stream. At the local level, revenue is primarily generated through property taxes. This spring, lawmakers are in session to adopt the state budget that will guide Texas for the next two years and public education represents the biggest share of the state’s general revenue spending.

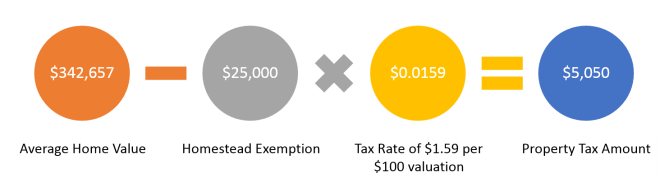

School funding is supported by taxpayer dollars and a new report released by the state comptroller indicated that roughly 38 percent of public education funding came from the state and 62 percent from local sources. But the overly complicated formula used for calculating funding to schools can be analogous to filling a glass of water – if I put more water in then you have to put in less; if you put more in then I have to put in less. This inverse relationship captures the essence of current debates as property values continue to skyrocket. Consider this for a moment, the average single family home value in our city in 2013 was $221,821; fast forward to 2018 and it’s $342,657, an increase of nearly 55%! Now let’s do some property tax math based on this figure and our current local school district tax rate:

In addition to this amount, property owners can have taxes levied by the city, county, and local university. Funding our schools is a shared responsibility although the state determines how much total funding each school district is allowed to have. The legislature has established a basic allotment per student and then a separate “tier” of funding for program enrichment which addresses students needing a continuum of special services. The goal is to ensure that a student’s ZIP code doesn’t determine his or her educational opportunities. Districts first use local tax dollars toward meeting this allowable amount. If a district is unable to raise the allowable funding level locally because it doesn’t have a wealthy enough property tax base, then state dollars fill the gaps. If a district is able to generate more funding locally than allowed by the state’s formulas, then the excess property tax revenue collected locally is “recaptured” or sent back to the state for redistribution to other school districts. This is what is known as the “Robin Hood” provision and arguably the rule that generates the most controversy.

Ben Franklin once said “an investment in knowledge pays the best interest.” Next time we’ll examine the evidence that supports this claim.